Investing in Japan: much more than just a bet on a global rebound

Jonathan Allum, one of the finance industry’s longest-serving and most experienced observers of the Japanese market, talks to Merryn Somerset Webb about what might happen next.

Merryn recently spoke to Jonathan on the MoneyWeek Podcast. Listen to the full interview here.

Anyone who has worked in the Japanese stockmarket in pretty much any capacity over the last 25 years will have read The Blah, a piece of daily research on all matters financial and relevant to investors in Japan. It hasn’t always been called The Blah: before my time in the market (I started my career as a Japanese equity broker in Tokyo), it was briefly The Daily Bullet and then The Daily Blah, before the “daily” bit was dropped (just in case every day was a bit too hectic). It has also been written under three different corporate umbrellas (most recently SMBC Nikko). However, there has been one constant – its author, Jonathan Allum.

A few weeks ago Allum retired. I’ve long been an admirer of The Blah, partly for its general excellence, but also because Allum is one of the few people I know in the market who looks at finance through the prism of what is actually happening, rather than what he reckons should happen. Too many of us are so convinced that one theory or the other on markets must be correct that we dismiss rather more money-making opportunities than we should (John and I are guilty of this on US technology stocks, for example). Allum, on the other hand, defines himself as a classic liberal in the Robert Frost sense: “a man too broad-minded to take his own side in a quarrel”. With that in mind, we set up a Zoom meeting to talk through his 30 years in the market – and what gems (rather than forecasts…) he might have to pass on.

Subscribe to MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Japan: the future of capitalism?

I ask him what kept him focused on the Japanese market (which hasn’t exactly been popular for the last 20 years) for so long. Partly the “nagging belief that other people weren’t doing it very well”. There’s a huge amount of data available in Japan to get to the bottom of, and a lot misreporting of that data. There’s also a lot to unpack in the irritating idea that Japan is somehow different from other countries. “Japan is different from other countries in certain ways and similar to other countries in certain ways. But if you focus on the differences, I think it’s more of an... analytical dead end, because you then can’t take the insights available to the rest of the world and apply them to Japan.”

There has also long been an idea that Japan becoming less different – by which proponents mean more like the US – is a good thing and even somehow “the end destination, for a capitalist economy”. That looks like an increasingly wrong-headed way to look at things. Not only is Japanese capitalism pretty similar to that of Korea and much of continental Europe, but its “stakeholder” focus – the idea that its community, suppliers and employees matter as much as shareholders do – is now something the US and UK talk about aspiring to. “One might be slightly sceptical about whether companies are being sincere in this, but the trend, if anything, does seem to be more in the stakeholder rather than in the shareholder direction. So in that sense, we are all turning Japanese.” Perhaps it is the US and the UK that have been the outliers, not everyone else.

This isn’t just about stakeholders. It is also about financial resilience, the thing that, in an age of Covid-19 disruption, shareholders should surely be putting high up their stock-picking checklists – particularly if they are income investors. Prior to the various crises of capitalism we have seen over the last decade, Japanese firms were constantly “derided for excess conservatism” – and for holding too much cash that could have been paid out as dividends in particular. There has been an element of “survivor bias” in that: the companies that went into Japan’s crisis at the end of the 1980s with lots of debt did not survive it. But it is also a long-term reaction to the miseries of the 1990s: Japan’s managers know you need a good level of balance-sheet resilience (low debt, some cash) if you want to be sure of being around long term.

Japan has been a play on global growth

The other important thing to know about Japan, says Allum, is that for all the talk of difference, if you look at the market as a whole (using not the “barbarous relic” that is the Nikkei, but the Topix index), it basically moves in line with global GDP – and has done since 1998. Allum divides the Japanese market into three periods. There was the “rocket phase” (up like a rocket from 1980 onwards); the “stick phase” (down like a stick from the end of the 1980s to 1998 – a period sadly coincident with my time working in the Japanese market) and the “mediocre age” (1998 to now). Lots of analysts look at the market in specifically Japanese terms, but the evidence suggests that, at least at a macro level and at least for the last 22 years of the mediocre age, that’s been pointless. Japan “tends to do well when the economy is recovering or is about to recover globally and vice versa”. It is nothing but “a function of economic growth”.

On the plus side, if you take the view that we are now on the way to some form of economic recovery, within the discounting period of markets – say nine months or so – Japan would seem to be quite a good bet and “certainly has an economic sensitivity which may well be useful”.

The twist since 2005 has been that the Japanese stockmarket, in addition to moving with the global economy, has also moved with the currency. When the yen is strong, the market is weak, and vice versa. This makes some sense given that lots of listed companies are exporters, but in Japan the closeness has been “just bizarre” – and it has meant that anyone looking at the market has had to be fixated on the currency too. The good news is that there does now seem to be “a conscious uncoupling between the two”. The Nikkei has been strong, but the yen has been too. It would “be nice” if this continued and we could see Japan being “endogenously rather than exogenously driven”.

Japan: a value investor’s paradise

All this chat about markets following economic growth is beginning to worry me. For years in MoneyWeek we have told you that in the long run you shouldn’t judge a market by how you expect economies to do, but on how you expect companies to do – and crucially, how much you pay for those companies. Valuation matters. Has Allum’s experience made a nonsense of that idea? Not quite, he says. There is a cyclical component, in that in Japan in the 1980s the market boomed as the economy boomed. In the end, however, valuations did matter: however much analysts found new ways to justify them, they were not justifiable – and they crashed (as is usually the case when valuations hit extremes).

There is also plenty of long-term evidence suggesting that, in Japan in particular, value investing does give you better long-term returns. Lots of investors have used it as nothing more than a proxy on global growth, without noticing that it is also a long-term stockpicker’s paradise. “Unfortunately, as is often the case with investing, and indeed life, when you finally think you’re going to crack something it all falls apart. In the last few years, stocks that are cheaper got cheaper, stocks that are expensive got more expensive.”

That might now begin to change, I say. After all, Japan is one of the few markets left in the world that looks cheap on absolute measures. “ I would agree with that,” says Allum, who reckons that when market history is recorded, the last decade will be seen as an “aberrational period”, at least in terms of the failure of value investing. We note that Warren Buffett appears to agree. After a long time apparently considering the matter he spent $6bn buying significant stakes in five Japanese trading companies (Mitsubishi, Mitsui, Itochu, Sumitomo and Marubeni) earlier this year.

Japan should do “relatively well”

So what next, I ask. Any predictions from the safety of retirement? Allum isn’t big on predictions. The thing is, he says, that in financial markets in particular, if you are really good you will be right 55% of the time and if you are really bad it could be 45% of the time. Mostly everyone is wrong more often than not. However, he does offer a few thoughts (“with a level of modesty”, he says).

First, the strength of equities suggests a level of global economic strength that is not reflected in the super-low bond yields around the world. “My suspicion, without in any way being alarmist about... bond market collapses or interest rates going through the roof, is that the trend in interest rates will be upwards.” Not long now and the days in which the German government was able “to borrow money for 30 years for less than nothing” will look like “an enormous anomaly… bond yields will go up, bond markets will go down. And I think that’s probably good for equity markets”.

And on the Japan front? “There are great hopes for Mr Suga and his various exciting-sounding economic initiatives,” says Allum, referring to Yoshihide Suga, Shinzo Abe’s successor as prime minister. “But recent Japanese history tells us that if you have a long-serving prime minister, like Mr. Nakasone, like Mr. Koizumi, he is typically followed by a number of short-lived prime ministers. Which, given that Mr. Suga is starting his reign at the age of 71…” That’s youthful by American standards, I say. Perhaps, says Allum, but mostly it’s considered a bit “old to reach the top of the greasy pole”: he may not be around long enough to get his policies going.

Does it matter? Not really, says Allum. We agree that, in the main, markets aren’t much bothered about politics (unless there is extremism of one kind or another on the go). All in all, says Allum, Japan should do “relatively well”. It’s not quite the ringing endorsement some readers will have been hoping for – but from a man who isn’t mad for predictions, it’s still a pretty positive one.

Merryn Somerset Webb started her career in Tokyo at public broadcaster NHK before becoming a Japanese equity broker at what was then Warburgs. She went on to work at SBC and UBS without moving from her desk in Kamiyacho (it was the age of mergers).

After five years in Japan she returned to work in the UK at Paribas. This soon became BNP Paribas. Again, no desk move was required. On leaving the City, Merryn helped The Week magazine with its City pages before becoming the launch editor of MoneyWeek in 2000 and taking on columns first in the Sunday Times and then in 2009 in the Financial Times

Twenty years on, MoneyWeek is the best-selling financial magazine in the UK. Merryn was its Editor in Chief until 2022. She is now a senior columnist at Bloomberg and host of the Merryn Talks Money podcast - but still writes for Moneyweek monthly.

Merryn is also is a non executive director of two investment trusts – BlackRock Throgmorton, and the Murray Income Investment Trust.

-

Coventry Building Society bids £780m for Co-operative Bank - what could it mean for customers?

Coventry Building Society bids £780m for Co-operative Bank - what could it mean for customers?Coventry Building Society has put in an offer of £780 million to buy Co-operative Bank. When will the potential deal happen and what could it mean for customers?

By Vaishali Varu Published

-

Review: Three magnificent Beachcomber resorts in Mauritius

Review: Three magnificent Beachcomber resorts in MauritiusMoneyWeek Travel Ruth Emery explores the Indian Ocean island from Beachcomber resorts Shandrani, Trou aux Biches and Paradis

By Ruth Emery Published

-

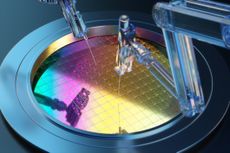

The industry at the heart of global technology

The industry at the heart of global technologyThe semiconductor industry powers key trends such as artificial intelligence, says Rupert Hargreaves

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

Three emerging Asian markets to invest in

Three emerging Asian markets to invest inProfessional investor Chetan Sehgal of Templeton Emerging Markets Investment Trust tells us where he’d put his money

By Chetan Sehgal Published

-

What to consider before investing in small-cap indexes

What to consider before investing in small-cap indexesSmall-cap index trackers show why your choice of benchmark can make a large difference to long-term returns

By Cris Sholto Heaton Published

-

Why space investments are the way to go for investors

Why space investments are the way to go for investorsSpace investments will change our world beyond recognition, UK investors should take note

By Merryn Somerset Webb Published

-

Time to tap into Africa’s mobile money boom

Time to tap into Africa’s mobile money boomFavourable demographics have put Africa on the path to growth when it comes to mobile money and digital banking

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

M&S is back in fashion: but how long can this success last?

M&S is back in fashion: but how long can this success last?M&S has exceeded expectations in the past few years, but can it keep up the momentum?

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

The end of China’s boom

The end of China’s boomLike the US, China too got fat on fake money. Now, China's doom is not far away.

By Bill Bonner Published

-

Magic mushrooms — an investment boom or doom?

Magic mushrooms — an investment boom or doom?Investing in these promising medical developments might see you embark on the trip of a lifetime.

By Bruce Packard Published