What the new US president means for your money

What does a Joe Biden presidency mean for your portfolio? The close-run election restricts Biden’s agenda – but certain companies will still do better than others, writes John Stepek.

Joe Biden is almost certain to be the next president of the United States. Donald Trump may fight for every inch, but unless there’s a huge surprise, then, come January, Biden will be sworn in. How much does that matter for investors?

Despite all the fuss that gets made about it, the occupant of the White House matters far less than lots of other factors. But there’s no doubt that a Biden presidency will be better for certain sectors, and worse for others, than a Trump win. So what should you be taking into account?

The state of the nation

The first question is how the land will lie once the dust has settled. It looks as though the Senate will stay in the hands of the Republicans. So Biden probably won’t be able to spend as much as he’d hoped on a “green new deal”. However, it suggests that we won’t see huge changes to taxation either. As John Higgins of Capital Economics notes, even if the Democrats do manage to take the Senate with “the slimmest of majorities, their more moderate senators would probably limit Biden to a more centrist legislative agenda”. So while less may be given with one hand, less will be taken away with the other.

Subscribe to MoneyWeek

Subscribe to MoneyWeek today and get your first six magazine issues absolutely FREE

Sign up to Money Morning

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Don't miss the latest investment and personal finances news, market analysis, plus money-saving tips with our free twice-daily newsletter

Of course, there are variations within that basic template. Whatever your views on him, Trump was undoubtedly a divisive leader, even within his own party. Some Republicans might be keen to distance themselves from him, and thus more willing to cooperate on certain issues – particularly as Biden has a reputation for bipartisanship, having worked closely with Mitch McConnell, the Republican Senate majority leader, in the past. In that case we might get more spending than expected. Alternatively, perhaps the Republicans may decide that continuing down the “Trumpism” route (albeit perhaps without Trump) is the key to winning in 2024, in which case they may be more obstructive than expected. If that happens, the Federal Reserve – America's central bank – will feel the need to step in and do more of the heavy lifting to prop up the US economy.

Fed boss Jerome Powell has already warned US politicians not to tighten the purse strings. In a pre-election speech, Powell urged the government to keep supporting businesses and unemployed workers through the pandemic. “Fiscal policy can do what we can’t, which is to replace lost incomes for people who are out of work through no fault of their own.” That said, Powell and the Fed are by no means powerless even if gridlock does prevent any further stimulus packages from being passed in the short term.

The Fed can still do yield curve control (pinning long-term bond yields to a specific low target – perhaps zero, as the Bank of Japan is already doing); it can still decide to buy lower-quality assets with quantitative easing – eg, copying the Bank of Japan again, in buying equity exchange-traded funds (ETFs); or turn interest rates negative (just like – you guessed it – the Bank of Japan). And even if Biden chooses to replace Powell, then his most likely pick for Fed governor will be someone even more inclined to money-printing, such as Lael Brainard, who is currently seen as his top pick for Treasury secretary.

So the only real question is how much fresh money comes in via the fiscal route, direct from the government (in which case it’s likely to be more inflationary), and how much comes in via the central bank route (which means it’s more likely to boost asset prices but not necessarily inflation). That said, some extra spending seems all but certain – we won’t see a return to fiscal conservatism any time soon.

What can Biden do?

Assuming that the balance of power implies gridlock, what difference can Biden make? The obvious area is in foreign policy, where the president has the most freedom to act alone. At the top of the list is China. As Tom Mitchell notes in the Financial Times, despite a sense that Trump’s legacy is one of trade wars, the trade representatives of the US and China have in fact managed to “turn trade into what is now arguably the most stable plank in [an] otherwise extremely fraught relationship”. Indeed, adds Mitchell, the China Daily newspaper noted after Biden’s victory that trade is “one of the last threads linking the two sides”. So Biden may simply continue as before – monitoring the results of the “phase one” trade deal which saw China agree to buy more commodities from the US, with a view to progressing to “phase two” next year.

That said, don’t expect relations to improve. For all that Biden is viewed as less volatile than Trump, that doesn’t necessarily mean less tension. Biden will revert to the more multilateral approach used in the past: gathering allies in Europe, North America and Asia to take a joint view under a weaker form of “Pax Americana”. The US will remain wary of China’s expansionism, particularly its growing belligerence towards Taiwan. A return to the “big umbrella” approach may leave China feeling more ganged up on by Western nations than under Trump’s more individualistic approach. As Biden himself put it: “When we join together with our fellow democracies, our strength more than doubles. China can’t afford to ignore more than half the global economy.”

But as Edward Luce notes in the FT, China may also provide Biden with the ideal way to sell investment in big infrastructure projects to his Republican rivals. Luce cites Thomas Wright of the Brookings Institution think tank: “They could find common ground with Republicans on industrial policy, infrastructure and many other areas if they place competition with China at the heart of their agenda.” And a more predictable approach to trade relations may help improve investor sentiment towards emerging markets more generally.

What are the investment implications?

What might all of this mean for your money? As my colleague Matthew Partridge wrote a couple of weeks ago, if Biden does get any kind of “green” stimulus through Congress, then it should be good for renewable energy stocks. That said, as Matthew also noted, the renewables sector has had a good run-up amid the general enthusiasm for all things ESG (environmental, social and governance), with one prominent solar fund up by about 40% in the last three months alone. So ironically, you might be better off looking to the fossil fuel sector as a play on a Biden win. That’s not just our contrarian, value-seeking mentality talking (though it helps). A “green” infrastructure deal might actively help the beaten-down energy sector.

Tighter regulation would not be good news for the fracking industry overall, for example. However, it would come just as low oil prices have already dealt a hammer blow to the sector. Conservation of capital is now the order of the day across the sector, which has already seen a great deal of consolidation. And if pumping out more oil via fracking becomes more difficult, then America’s status as the swing producer – which helps to keep oil prices capped – will be in doubt. In turn, that could send oil prices a lot higher, which would be good news for the more traditional oil companies. Those stocks have already enjoyed a big bounce on the back of the vaccine news but there could be a lot more to come if it turns out that there’s more life in fossil fuels than many now think. Obvious candidates for your portfolio include BP (LSE: BP), Royal Dutch Shell (LSE: RDSA), and Exxon (NYSE: XOM), which remains the most stubbornly committed to oil of all the majors. Or you could bet on US energy stocks as a whole via an ETF – the SPDR S&P US Energy Select Sector UCITS ETF (LSE: SXLE) tracks the big S&P 500-listed US energy companies.

A convenient London-listed option for those who expect more spending on US infrastructure is the iShares Global Infrastructure UCITS ETF (LSE: INFR). Despite the “global” badge, about two-thirds of the ETF is invested in US stocks, with a wide range of investments that cover renewables, telecoms (for all that 5G spending) and railways (if you’re betting on an infrastructure boom you need to get all those materials across the states somehow). If you’re keen to choose individual stocks, Charles Lewis Sizemore in Kiplinger suggests Martin Marietta Materials (NYSE: MLM) which specialises in vital building materials such as concrete, sand, and gravel; and construction equipment giant Caterpillar (NYSE: CAT).

On the healthcare front, Sizemore reckons that health insurer UnitedHealth Group (NYSE: UNH) could be a good bet because it “specialises in Medicare supplemental plans”, which could benefit from any successful expansion of the scheme. A more esoteric option is to bet on further moves towards the legalisation of cannabis in the US, particularly at a federal level. That would make it easier for such businesses to access funding (even when cannabis is legal in individual states, banks are reluctant to fund a business that remains illegal at a federal level). By investing in the Medical Cannabis and Wellness UCITS ETF (LSE: CBDX), UK-based investors can get exposure to a “basket of companies from developed and emerging markets with high exposure to the medical cannabis, hemp and cannabinoids (CBD) industry,” notes the provider, HANetf.

As for stocks to avoid – the banking sector regarded a Biden win with some trepidation due to the scope for higher taxes and more regulation, but neither of those seem as likely now, so we wouldn’t shun financials by any means (particularly if inflation is about to turn). However, the tech sector has been under a lot of scrutiny lately, and that’s only likely to continue as US politicians of all stripes raise concerns about the influence and dominance of the sector. That said, if tech stocks really have reached the end of their present boom cycle, it’ll be due to a more fundamental shift in the interest rate cycle rather than any explicit policies Biden pushes through.

John is the executive editor of MoneyWeek and writes our daily investment email, Money Morning. John graduated from Strathclyde University with a degree in psychology in 1996 and has always been fascinated by the gap between the way the market works in theory and the way it works in practice, and by how our deep-rooted instincts work against our best interests as investors.

He started out in journalism by writing articles about the specific business challenges facing family firms. In 2003, he took a job on the finance desk of Teletext, where he spent two years covering the markets and breaking financial news. John joined MoneyWeek in 2005.

His work has been published in Families in Business, Shares magazine, Spear's Magazine, The Sunday Times, and The Spectator among others. He has also appeared as an expert commentator on BBC Radio 4's Today programme, BBC Radio Scotland, Newsnight, Daily Politics and Bloomberg. His first book, on contrarian investing, The Sceptical Investor, was released in March 2019. You can follow John on Twitter at @john_stepek.

-

Barclays warns of significant rise in social media investment scams

Barclays warns of significant rise in social media investment scamsInvestment scam victims are losing an average £14k, with 61% of those falling for one over social media. Here's how to spot one and keep your money safe

By Oojal Dhanjal Published

-

Over a thousand savings accounts now offer inflation-busting rates – how long will they stick around?

Over a thousand savings accounts now offer inflation-busting rates – how long will they stick around?The rate of UK inflation slowed again in March, boosting the opportunity for savers to earn real returns on cash in the bank. But you will need to act fast to secure the best deals.

By Katie Williams Published

-

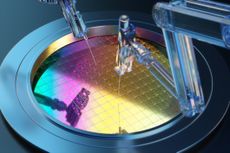

The industry at the heart of global technology

The industry at the heart of global technologyThe semiconductor industry powers key trends such as artificial intelligence, says Rupert Hargreaves

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

Three emerging Asian markets to invest in

Three emerging Asian markets to invest inProfessional investor Chetan Sehgal of Templeton Emerging Markets Investment Trust tells us where he’d put his money

By Chetan Sehgal Published

-

What to consider before investing in small-cap indexes

What to consider before investing in small-cap indexesSmall-cap index trackers show why your choice of benchmark can make a large difference to long-term returns

By Cris Sholto Heaton Published

-

Why space investments are the way to go for investors

Why space investments are the way to go for investorsSpace investments will change our world beyond recognition, UK investors should take note

By Merryn Somerset Webb Published

-

Time to tap into Africa’s mobile money boom

Time to tap into Africa’s mobile money boomFavourable demographics have put Africa on the path to growth when it comes to mobile money and digital banking

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

M&S is back in fashion: but how long can this success last?

M&S is back in fashion: but how long can this success last?M&S has exceeded expectations in the past few years, but can it keep up the momentum?

By Rupert Hargreaves Published

-

The end of China’s boom

The end of China’s boomLike the US, China too got fat on fake money. Now, China's doom is not far away.

By Bill Bonner Published

-

Magic mushrooms — an investment boom or doom?

Magic mushrooms — an investment boom or doom?Investing in these promising medical developments might see you embark on the trip of a lifetime.

By Bruce Packard Published